Asylum

Too often, immigrants who are seeking asylum in the U.S. are prosecuted as criminals in Streamline courts. The End Streamline Coalition believes that this is illegal as well as immoral. The U.S. should protect asylum seekers, not prosecute and incarcerate them.

What Does the Law Say About Asylum Seekers?

International Law

Following World War II, the United Nations created the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that recognized the right to seek asylum from persecution in other countries. The U.N. incorporated this principle into the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1951 which was later amended as the 1967 U.N. Protocol. The United States was a signatory to the 1967 U.N. Protocol and thus is bound by its provisions.

U.S. Law

The U.S. incorporated the U.N. asylum definitions into its own law in the Refugee Act of 1980. U.S. law says that any immigrant who is fleeing persecution and enters the U.S. may apply for asylum, whether or not they entered the U.S. at a port of entry. [“Read more”– https://americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/asylum-united-states

Criteria for Asylum

People who are seeking refuge in the U.S. may qualify for asylum if they have experienced persecution or have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country due to:

- Race

- Religion

- Nationality

- Membership in a particular social group

- Political opinion

Protection for Asylum Seekers

Two important legal and human rights principles for protecting asylum seekers include:

- Asylum seekers should not be punished for seeking refuge in another country(1951U.N. Convention on Refugees and U.N. 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees).

- Asylum seekers should not be returned to their home country without determining if they have a valid asylum claim.(1951U.N. Convention on Refugees; U.N. 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees; U.S. Refugee Act of 1980).

How Is the U.S. Asylum Process Supposed to Work?

When immigrants enter the U.S. at a port of entry or in other ways, they can tell a Border Patrol agent or other official that they are seeking asylum in the U.S. The U.S. official should document this and follow procedures to ensure that the immigrant’s asylum request is evaluated fairly. The process is complex but includes these steps:

- An initial screening known as a Credible Fear or Reasonable Fear interview conducted by an immigration official. If individuals fail this screening, they may be deported. They may also appeal the ruling.

- Immigrants who pass the initial screening may present their asylum case before an immigration judge. There may be a long wait because immigration courts have lengthy backlogs.

Asylum-seekers must be able to present convincing evidence that they have a“well-foundedfear of persecution” in their home country due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

What Really Happens to Immigrants Seeking Asylum in the U.S.

Customs and Border Protection officials at ports of entry sometimes turn away asylum seekers, falsely claiming that the U.S. will not accept them. Border Patrol agents who apprehend border crossers sometimes ignore or dismiss immigrants’ requests for asylum and fail to document it. Agents may use the threat of family separation as means to deter asylum seekers traveling with children.(Link– https://www.hopeborder.org/sealing-the-borderAnother link: http://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/Barriers%20To%20Protection.pdf

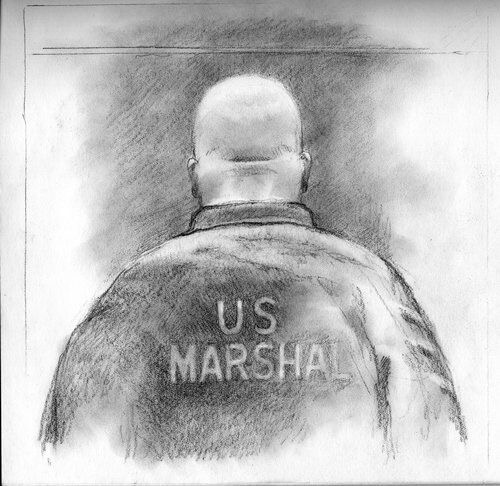

Individuals who attempt to enter the U.S. without authorization are regarded as law-breakers and are prosecuted as criminals, even if they have come to the U.S. to seek asylum. This violates international prohibitions against punishing asylum-seekers.

During the prosecution process, the immigrant’s request for asylum and right to a credible fear screening interview may be ignored or lost in the maze of detention and prosecution.

The U.S. often incarcerates asylum seekers during the asylum process, even those who presented at a port of entry and are not being criminally prosecuted. This means that asylum seekers who passed initial screening interviews and are waiting to present their case to an immigration judge may be in an immigration detention center for as long as two years or more.

What Happens to Asylum Seekers Who are Prosecuted in Streamline?

Border Patrol

When Border Patrol agents apprehend migrants, they are supposed to ask whether the border-crosser entered the U.S. to seek asylum, but this happens inconsistently. Immigrant rights groups have documented numerous occasions when Border Patrol agents ignore or disparage migrants who say they are fleeing violence and oppression in their home countries. Link: http://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/Barriers%20To%20Protection.pdf

Defense Attorneys

Apprehended migrants, including asylum-seekers, who are selected for prosecution via Streamline will be bussed to the courthouse on their court date, and will meet with an assigned defense attorney in the morning for about 30 minutes. In this limited time, the attorney should proactively ask defendants about their reasons for entering the U.S., explain the process, and offer counsel. The attorney should document the asylum request and take steps to ensure that the defendant will get a credible fear interview.

Rapid Deportation

First-time border-crossers in Streamline usually get a sentence of time served, and will be deported quickly back to their home country. The migrant’s status as an asylum-seeker may be missed or ignored, with no credible fear interview.

- An initial screening known as a Credible Fear or Reasonable Fear interview conducted by an immigration official. If individuals fail this screening, they may be deported. They may also appeal the ruling.

- Immigrants who pass the initial screening may present their asylum case before an immigration judge. There may be a long wait because immigration courts have lengthy backlogs.

Asylum-seekers must be able to present convincing evidence that they have a“well-foundedfear of persecution” in their home country due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

How Many Immigrants Who Apply for Asylum are Successful?

- Success rates for passing credible or reasonable fear interviews vary by region and by the immigration official who does the interview.

- Those who pass their screening interview will wait one-to-two years before their case is heard by an immigration judge. During this time, asylum-seekers and their family members may be detained in an immigration detention center.

- Success rates vary by country of origin and the region of the U.S. where the case is heard. For example, in 2016, 30% of Chinese applicants were successful, compared with 10% from Guatemala and 7% from Honduras.